How to ruin a good thing |

| We recognize a mind only by the bodily expressions of an autonomous agent. If we think about a specific mind, we always think about a person we are more or less familiar with. This person expressed his or her feelings in a way recognizable to us, either intentionally, or even without taking any notice of us. We may be familiar with that person's voice (even written words might be sufficient), with that person's face, figure, gestures. All these signs exhibited towards the outer world are a composite of explicit and implicit behavior. |

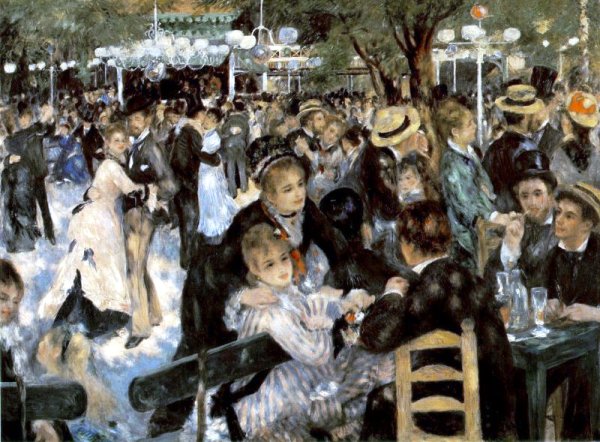

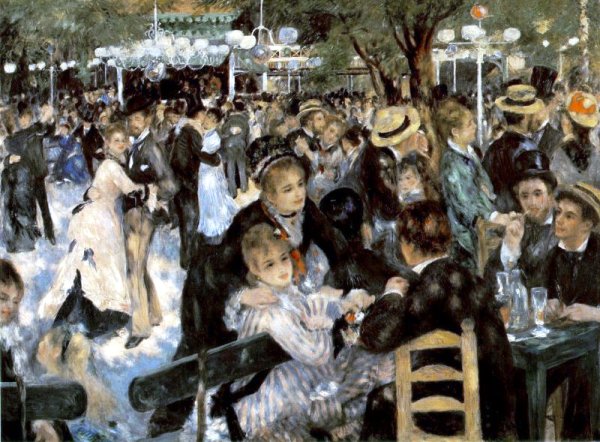

| The explicit part of a person's behavior is the result of a conscious decision. For the most part of a routine day we don't need that kind of behavior. The implicit part of a person's behavior is the result of life-long learning, training and adaptation. Therefore, this part of behavior not only has to do with a single person, but also with a person's history, environment, family, experiences since childhood. Since we exhibit for most of our time this latter type of behavior, grown native societies in general evoke typical, recognizable impressions and 'atmospheres', resulting from the multiple replication of behavioral stereotypes (Centola & Baronchelli 2015). |

| Each society transmits a typical wealth of knowledge, basic behaviors, routines, rules, customs, ways of living. Becoming part of a society means to adopt this legacy to some extent. Routes of transmission, however, have changed dramatically over the last generations. While a few generations ago the habits of a community had the chance to develop locally, keeping in decent harmony the needs, desires and anxieties of its members, in modern times mass media, tele-communication and the ease of global transportation of goods and humans have torn down the natural barriers of information transmission. |

| While in former days, communication was largely dependent on personal physical contact, we receive today the greatest part of daily information influx via anonymous channels, neither inviting and mostly not even enabling immediate feedback. We still receive feedback from our immediate environment, however, this environment is no longer the exclusive, not even predominant source of relevant information. Therefore, we feel less responsible towards our physical neighbors and prefer to direct our attention towards agents offering distraction and amusement without claiming troublesome investments from our side. |

| Our physical appearance, how we position and move our own body, the clothing we deem appropriate, the style of our hair, the timbre of our voice, the words we select, all this and much more makes us recognizable to our fellow-men. Still we owe most of the repertoire from which we select our minute-to-minute comportment to the first few years of our life spent in an intimate family atmosphere. However, most of our modern societies cease to compose these individual atmospheres into consistent communal atmospheres, encompassing the numerous families of a society. We are witnessing today the loss of a precious, irretrievable good. |

| This good has grown over millenia, but is easily ruined within decades. Before we allow this to happen, we had better learn what it was good for. Is cultural diversity really dispensable? Will it be possible to replace the multiple cultures of the world by a single global one (Buchan et al. 2009)? What should such a global culture look like, and how could we assist its tradition? Will all members of a 'global society' feel responsible to those they are in contact with? As long as convincing (positive) answers to these questions are missing, we should carefully preserve the cultural diversity of our world. |

| Rather than positive ones, brain research, cognitive neuroscience and anthropology provide mostly negative answers to all these questions (see e.g. Efferson et al 2008). Since we signal to our fellow-men largely by implicit cues we are not directly aware of, the major part of our communication is lost if reduced to tele- communication. Even worse, an increasing fraction of modern societies is exposed to one-way visual and auditory channels, i.e. sensory-deprived information that is forced upon them, with very poor options to react. By this, major parts of the population are lost for the active fostering of culture. |

| What kind of 'global culture' can we expect to develop from such poor-quality and asymmetric modes of communication? Although it has to be acknowledged that a loss of cultural diversity may reduce tensions (Buchan et al. 2009), I have my doubts that happy people will be the result. |

| 8/08 < MB (8/08) > 10/08 Freedom & Society ...and still more. |

| D

Centola & A Baronchelli (2015) The spontaneous emergence of

conventions: an experimental study of cultural evolution. Proc Nat Acad

Sci USA 112:1989-94 NR Buchan, G Grimalda, R Wilson, M Brewer, E Fatas, M Foddy (2009) Globalization and human cooperation. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA 106:4138-42 C Efferson, R Lalive, E Fehr (2008) The coevolution of cultural groups and ingroup favoritism. Science 321:1844-49 |