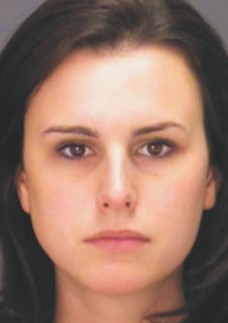

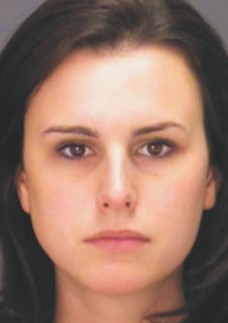

(Taken from Kampe et al. 2001)

|

Hey you... (Taken from Kampe et al. 2001) |

| Among the pleasures accessible to humans (and most non-humans too), sexual pleasures occupy an exceptional position. Here, the object of desire is no food, no drink, no drug, no warm place at the fireside, no spectacular landscape view, no thrilling sound, nothing of this kind. Here, the object of desire is another human being. Thus, humans not only are potential subjects of this feeling, they all are potential objects too, and this makes a significant difference in comparison to other more innocent amusements. |

| Each good looking human, by his/her mere existence, is a potential source of pleasure for other humans, even if the contact is limited to informal eye contact. Imaging studies have demonstrated that the returned eye gaze from an attractive face increases oxygen consumption in the ventral striatum, a brain area associated with reward prediction (Kampe et al. 2001), while returned eye gaze from an unattractive face had the contrary effect. The authors conclude that this response reflected an automatic evaluation of the likely reward that can be derived from conspecifics. In an open setting, good looking humans will attract more eyes than others, increasing their chance to catch the glances of other good looking humans and, finally, increasing their chance for reward. |

| However, to a large extent it’s no one’s merit to look good. It is well established that symmetry and averageness in the outer appearance of an individual is perceived as beauty and renders a greater mating success (Grammer & Thornhill 1994; Gangestad & Simpson 2000). Intuitively, we would have expected more to hide behind our romantic feelings, but the sober truth is that preferring symmetric bodies of average appearance decreases the likelihood to fall for rotten genes. Asymmetry is believed to reflect deviations in developmental design resulting from the disruptive effects of environmental or genetic abnormalities. Therefore, we act as enterprising salesmen and horse-dealers rather than as Romeos and Juliettes in our affaires, and not all humans are equal in their chance to profit from rewarding interactions with conspecifics. Some individuals are spoiled by nature with better pre-conditions than others. As a consequence, they more likely will engage in rewarding interactions with other superficially privileged individuals. |

| In human society, the drive to secure pleasure from sexual intercourse is traditionally subjected to strict regulations. Several behaviors, as rewarding as they might appear for the subject as a physical act, are threatened by punishment, in the first place to protect objects plagued against their will. However, a society’s attitude against certain sexual habits goes far beyond the banishment of violence. In many socio-cultural settings, long-term traditions encompassing hundreds of generations stigmatize the public exhibition of sexual pleasure. Similarly, in most societies the explicit hunt for sexual contacts is greeted with disdain. Why is that so? And why do sexual encounters usually take place in seclusion, withheld from the eyes of witnesses? Why so often do lovers have the feeling, they shouldn’t do what they are doing, and want to be sure that nobody else can see or hear them? |

| The fact that one of the most blessed and joyful experiences humans are capable of, is often subjected to stern regulations, might appear as a paradox. However, most pleasant behaviours are the target of rules, mostly to prevent abuse. In the case of sexual pleasure, the injunction to hide its enjoyment from the public may have had additional reasons. Primates, and especially humans, stand out in their ability to take into account what others are thinking (Adolphs 2003). Appreciation of humour, social-norm transgression resulting in embarrassment, viewing erotic stimuli, and eliciting of other moral emotions, all activate the medial prefrontal cortex (reviewed in Adolphs 2003). Several studies assign to the medial and the orbital prefrontal cortex a role in guiding the strategic adoption of someone else’s point of view (“theory of mind”, Gallagher & Frith 2003). Human brain diseases are known, featuring reduced (autism) or increases sociability (Williams syndrome). |

| In societies with long-standing tradition, altruistic behaviours confer a high reputation. Human altruism is a powerful force and is unique in the animal world. Whether altruism evolved only culturally or as a result of gene-culture co-evolution is still a matter of debate (Fehr & Fischbacher 2003). In philosophical terms, human altruism could be summarized as Kant’s imperative, to refrain from activities perceived as harmful, irritating or annoying if exhibited by others towards us. The impulse to conceal the experience of sexual or erotic pleasure might originate in the intention to avoid the instigation of envy and jealousy in others. From our own experience, we classify such feelings as negative and distressing. Recurring to our cognitive faculty “theory of mind”, we are able to deduce that others suffer the same feelings as we did in a comparable situation. |

| In the lifetime of a human being, he/she has ample opportunities to experience how it feels to be mistreated or offended by others. Falling in love with someone is a powerful experience leaving distinctive marks in the brain (Bartels & Zeki 2000; 2004; Balaban 2004; Najib et al. 2004), and love disappointed by a superficial, unfaithful partner is one of the most harmful experiences a human can come to know. The devaluating attitude of societies with long-standing traditions against individuals exploiting their physical attractiveness to actively attract multiple partners, might originate from a collective social attempt to protect the majority from emotional harm (altruistic punishment, Fehr & Gächter 2002). Human behaviour is rewarded or punished by social conventions, depending on the consequences for other humans. And behavior with positive consequences for the actor, but negative ones for most others, is banned by most societies. It’s a sin. |

| Adolphs R (2003) Cognitive neuroscience

of human social behaviour. Nat Rev Neurosci 4:165-178 Balaban E (2004) Why voles stick together. Nature 429:711-712 Bartels A, Zeki S (2000) The neural basis of romantic love. NeuroReport 11:3829-3833 Bartels A, Zeki S (2004) The neural correlate of maternal and romantic love. NeuroImage 21:1155-1166 Fehr E, Fischbacher, U (2003) The nature of human altruism. Nature 425:785-791 Fehr E, Gächter S (2002) Altruistic punishment in humans. Nature 415:137-140 Gallagher HL, Frith, CD (2003) Functional imaging of ‘theory of mind’. Trends Cog Sci 7:77-83 Gangestad SW, Simpson JA (2000) The evolution of human mating: Trade-offs and strategic pluralism. Behav Brain Sci 23:573-644 Grammer K, Thornhill R (1994) Human Facial Attractiveness and Sexual Selection: The Roles of Averageness and Symmetry. J Comp Psychol 108:233-242 Kampe KKW, Frith CD, Dolan RJ, Frith U (2001) Reward value of attractiveness and gaze. Nature 413:589 Najib A, Lorberbaum JP, Kose S, Bohning DE, George MS (2004) Regional brain activity in women grieving a romantic relationship breakup. Am J Psychiatry 161:2245-2256 |