Too far away to know? |

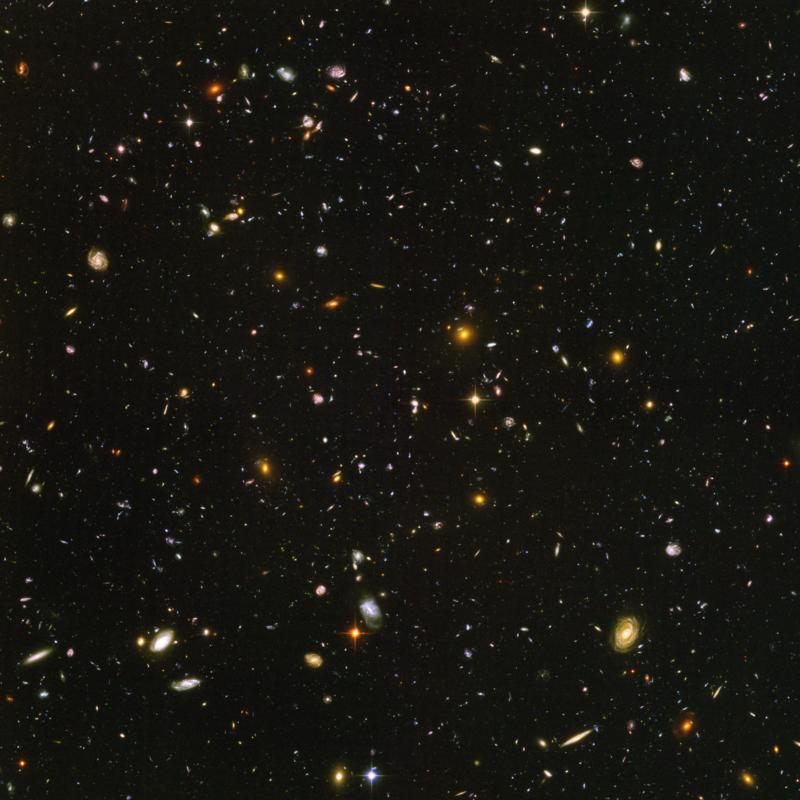

Like goldfish in a bowl, this image, taken in visible light by the Hubble Space Telescope, shows a plethora of galaxies billions of light years away in a random patch of sky called the Hubble Ultra Deep Field (Wirth 2004). |

| Most cosmologists agree in estimating the age of our universe at 13.7 ± 0.2 billion years (don't ask me how they do). Although there has always been considerable debate on that question (Chaisson 1997), several recent observations allowed to narrow this estimate down to this astonishingly precise number, given the long time period that has elapsed since the Big Bang. Advanced recording techniques allow the detection of faint light signals from objects that are really far away, up to 10 billion light-years, and even more (Wirth 2004). More? |

| Wait a minute... More than 10 billion light-years away?! What was the age of the universe, again? If we have knowledge of objects out there, more than 10 billion light-years away, wouldn't that mean that these objects, during the last 13.7 billion years or so, had nothing better to do than to move away from us as fast as Albert Einstein would have allowed them to do? And - to make things worse - since this information comes to us by light, we only learn where these objects have been more than 10 billion years ago. Where the hell might they be now, 2005 years after the birth of our savior Jesus Christ? |

| We discover many mysteries while staring into the sky, but true observation is one thing, and mere extrapolation another. Of course we might conclude that these far away objects have traveled in the meantime another considerable distance, surely more than we are able to walk by foot in a lifetime, but there is no way to obtain any information on their actual position. They might have even disappeared in the meantime, and according to the laws of physics we would not have the slightest chance to find out. |

| So, the observable space around us is smaller than our imagination is dreaming of. While looking at the moon, we can be sure that it existed 1 second before, but nobody can tell us for sure if he still exists at the very moment we are looking at it. Likewise, if God the Almighty would come to the idea to switch off the sun, just as we would do with the bathroom light if we noticed we left it on unintentionally, we wouldn't realize it before 8 minutes had passed. Thus, we only know that the sun existed and was shining 8 minutes ago, we impossibly can have any information on its actual state. The actual state of the sun and of the moon is beyond our observability, it is not part of our observable world. The continuation of their existence into the moment we are experiencing as "now" is just a (nevertheless plausible) hypothesis. |

| Our observable reality outside of good old mother earth consists of a moon as it was 1 second ago, of a sun as it was 8 minutes ago, of a few planets as they've been minutes to hours ago (not to mention a handful of comets swarming around), of several stars as they were many years ago, of myriades of other stars as they were thousands of years ago, and - with the aid of powerful instruments - of myriades of galaxies as they were up to more than 10 billion years ago. Galaxies at the far end of the universe as they might be today are not part of our observable reality (in spite of what Lineweaver & Davis claim in their recent Sci-Am review). Without direct observation, their present state cannot be labeled as "existing" or "non-existing". Speculating about their actual state is equivalent to speculating about the future state of our closer environment: Their "present time" is for us as inaccessible as our future. |

| From a quantum theoretical point of view, the present location of a distant galaxy is equivalent to the probability distribution of a particle that can be broken down to reality only by measurement and observation. As long as no data have been obtained, its location remains a smear over all possible locations, including even its frank non-existence (even if we actually wouldn't have any theory at hand to explain for such a disappearance). By that, however, nothing mysterious or awkward is to be said about these distant galaxies because, from their point of view, we are just as distant from them as they are from us, and we surely would not appreciate our Milky Way to be discredited as "smear of possible locations". |

| What is "reality", and what is "now"? If we touch a thing, we act on it, and we obtain feedback immediately. This is our gold standard for reality. Many things that undisputedly are part of our reality cannot be touched, like the clouds in the sky, and like the sun. Where is the boundary? |

On the border between fiction and reality

| E.J.Chaisson (1997) Cosmic age controversy is overstated. Science 276: 1089-1090 |

| C.H.Lineweaver & T.M.Davis (2005) Misconceptions about the Big Bang. Scientific American March 2005, 36-45; or: Der Urknall: Mythos und Wahrheit. Spektrum der Wissenschaft Mai 2005: 40-47 |

| G.D.Wirth (2004) Old before their time. Nature 430: 149-150 |

| E-mail comment by Tamara Davis (Research School of Astronomy and Astrophysics, Australian National University, Canberra, Australia): |

| Hi Michael, |

| Yes, I agree that what you choose to call the observable universe is a matter of definition. You've chosen to put a time constraint on the definition, whereas most scientific literature chooses to define something as observable if we have ever been able to observe it. I'm in agreement with much of what you've written, but if you read our article carefully we never claim that "galaxies at the far end of the universe AS THEY MIGHT BE TODAY" are part of our observable reality. In fact we are quite clear that we see these objects only as they were long ago. Nevertheless the definition in common scientific usage calls these galaxies part of our "observable universe" even though we can only see them as they are long ago. |

| Regards,

Tamara |

| p.s. If you want to use the best example of seeing things that are far away use the cosmic microwave background. It was emitted about 13.7 billion years ago* and is now 46 billion light years away, so is much further than the galaxies we're seeing as they were 10 billion years ago. |

| * Strictly speaking: about 379.000 years later, at the time the universe is supposed to have become transparent to light; see my essay Looking at the bottom of time (MB). |