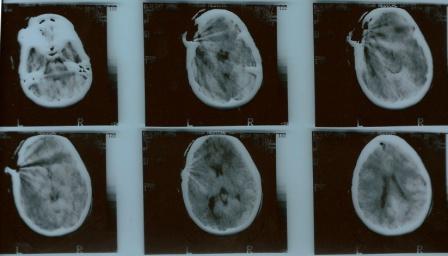

| The result came as a shock to JS: Encephalomalacia in the left frontal lobe

and mild T2 hyperintensity within the left middle frontal gyri. These anomalies

were minor but consequential. They partly (if not fully) accounted for the

behavioral anomalies that had prompted this imaging investigation. In the

following years, JS received social security support, first in Minnesota, later

in California (where she had spent most of her childhood and part of her

youth). |

| Unable to decide on her further living, JS began to travel the world.

Although mentally handicapped, she was able to profit from high cognitive

aptitudes and skills. Grown-up as a bilingual (English & Hebrew), she

easily acquired further languages: French, Portuguese, and starting with 2006

German. In 2006, we met in Vienna (Austria). At that time I was in charge to

organize in Austria the International ‘Brain Awareness Week’ of the ‘Dana

Alliance for the Brain’. JS found us in a DANA magazine and on the internet and

offered to donate her brain for research purposes. Insecure how to react to

such a sinister offer, we replied that at least we would have to wait for her

death… When she arrived at Vienna (to learn German, as she said), I quickly

found out that she was not about to die so soon at all. As a brain researcher,

I became interested in her case. I was perplexed by this coexistence of a

highly functional personality with subtle behavioral defects that become apparent

only upon closer attention. JS asked me to explain to others, what kind of

defects these are. This is the reason for this text. |

| So: what kind of mental defects JS is suffering from? To understand these

defects, we need to delve into the functional architecture of the human brain. This

is the most complicated of our organs, nevertheless great advances have been

made in the exploration of its functioning, also thanks to the careful

observation of cases like JS. What exactly happened to JS’s brain on February

25th in 1984, when the car she was in on the back bench left the

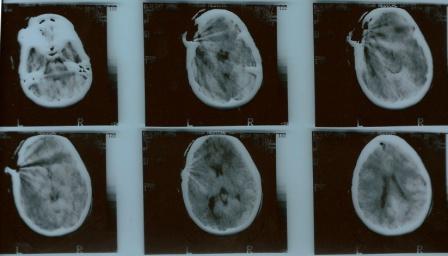

road so unduly and fell 10 m into a ditch? The medical exposé of the Rambam

Medical Center in Haifa where the victim was rushed to reads as follows: |

| Deep wound on left forehead, from eyebrow to parietal area, pulsing dura

exposed, subdural air. Operated under general anesthesia, small tear in dura,

minimal contusion below. Wound closed without reconstruction of skull defect.

Superficial consciousness for 2½ days. Release after 8 days, no overt

neurological deficits. |

| This last remark stirred hopes in the family that JS, then 9½ years old and

such a beautiful and charming girl, would have been lucky and would recover

fully from this severe incident. But the neurosurgeon should have known better.

He had seen pieces of broken bone, subdural air, and the small tear in the

dura. These observations leave little doubt that the injury had affected not

only the skull but also the brain tissue below. And behind the eyebrow lies the

orbitofrontal cortex, getting its name by its tight contact with the orbit, the

bony cavity harboring the eye. It is no surprise that another deficit remaining

from this injury was a partial loss of eyesight on the left side. |

| The orbitofrontal cortex belongs to the ‘prefrontal cortex’, the ‘pre-‘

indicating that this area lies ahead of those frontal areas that are

responsible for our motor and sensory functions. Lesions to one of these

anterior regions have no overt consequences on motoric or sensory functions. On

first glance, the patient may appear unaffected. A famous historic example is Phineas

Gage who in 1848 lost his left eye and parts of his left prefrontal cortex at

the age of 25 during a working accident. Against the common narrative that Mr.

Gage after the incident had turned from a decent gentleman into a bad-mannered,

hard drinking and highly unreliable villain, the injured recovered

astonishingly well, serving for 8 years a demanding job as a long-distance

stagecoach driver in Chile. The injury of JS is much smaller and more

localized. The accident did not result in a loss of brain tissue, but

disconnected parts of the left orbitofrontal cortex from its regular

addressees. Which connections have been affected in detail cannot be told from

the structural MRI scan. In addition, we still do not fully understand all

functions of the human orbitofrontal cortices (furthermore, the left and the

right one seem to serve slightly differing tasks). As a preliminary working

hypothesis, the neuroanatomical position of these gyri suggests a role in

connecting the prefrontal cortex to the so-called ‘limbic system’. |

| The different parts of the prefrontal cortex occupy the highest level in

cerebral information processing, not under direct sensory or endocrine influence.

Their genuine task seems to consist in overseeing and coordinating lower level

activities. Therefore, they are often said to harbor our reason. Since the

orbitofrontal cortex sustains connections to the limbic system mostly dealing

with emotions like joy, anger, fear, sadness and disgust, it is assumed that

this high level area somehow integrates our feelings into reasonable thinking.

Thanks to reasonable thinking, we can resist impulses telling us to immediately

follow our actual spontaneous inclinations. For example, it will be wise to

treat our neighbor politely, then he will probably be helpful if we get in

trouble. Reason acts with foresight and is able to withhold the reasonable from

giving way to attractions leading to transient rewards with unfavorable long-term

consequences. The most important addressee in the limbic system for the

orbitofrontal cortex seems to be the amygdala. The most prominent feeling

elicited by amygdalar activity is fear. Undisturbed interplay between the

amygdala and the orbitofrontal cortex informs our reason about the emotional

(negative) value of a fearful face. If this interplay is handicapped, the

afflicted has difficulties to attach emotional value to impressions that

normally would be classified as fearful. Social learning is at the heart of our

behavioral development. Children strongly depend in their habit formation on

social feedback. They have to interpret continuously social cues as positive or

negative, disclosed to them often in casual and informal settings. Smooth

interplay between the prefrontal cortex and the limbic system provided, these

social interactions will occur without much effort or the need to pay focused

attention to them. |

| Having laid out these – in part still speculative – neurobiological

background, we might now be in the position to understand, how a rather limited

lesion in the left orbitofrontal cortex should lead to difficulties to comply

with social norms. If the lesion occurred at some later stage of development

(as in the case of JS at the age of 9½ years), many basic habits have already

formed. They probably will persist although it is not totally clear to which

extent their persistence depends on the continued input of information. On the

other hand, many habits typically acquired only during puberty and early

adulthood will be much more difficult to form. It will not be sufficient simply

to see an angry face as guidance into the complex realm of dos and don’ts. New

habits in compliance with social norms will only form upon patient and often

repeated explanation and logical argument. We cannot take the easy way from the

limbic system to reason, going by the amygdala and the orbitofrontal cortex.

This path is not fully operating in JS’s left hemisphere. If others understand

some social relationships and facts of increasing complexity by a simple, less

than friendly glance, JS needs the full program: proof or disproof, detailed

material, majority and minority opinion, examples, exceptions, and so forth. For

her social contacts, this disposition may in the long term be tiresome and

irritating. Probably she will have problems making friends, but more sincere

friends may appreciate her serious and diligent approach to matters of sometimes

daunting complexity. She has no fear of complexity, even if surrounded by warning

social cues. The prefrontal cortical areas in JS’s brain are very well in the

position to fulfil their internal functions, even if one of them is not working

well. Sometimes, it may even be of advantage if the ‘traffic between reason and

feelings’ is not running so smoothly. Then, the intact rest of the prefrontal

cortex can deal with matters without being disturbed by emotions (which all too

often are of transient or even redundant significance). This sometimes allows JS

to accomplish impressive feats requiring a high level of deliberation and

synthesis. |

| Let’s have Brita a final word on JS, a sincere friend during her time at St. Olaf sharing a room with her back in

the 90ies (the comment is from June 06): |

| “…her priorities and the

way she thought about things were unique… She particularly had trouble with

authority figures when she conflicted with them… I also noticed that she would

learn in unique ways as well. She excelled in anything that required

memorization or detail oriented work, but things that required integration of

information was baffling to her. I remember talking to her about a French class

we were taking together. She was having a very difficult time reading a book in

French because she would have to stop and define every single word that she

didn’t know. She was unable to figure them out from the context, or get the

gist of the story even though her vocabulary was far above average. … She is

exceedingly logical and has a hard time identifying or understanding her

emotional world. Everything must be explained and explored to a great degree

before she is comfortable with it. …” |