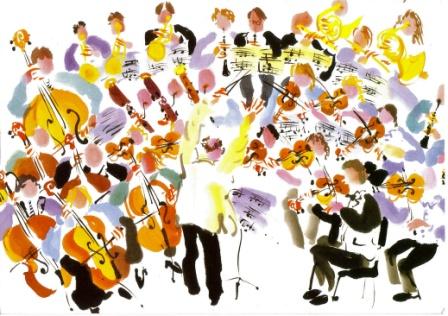

The improving orchestra

|

| Why

are older people more forgetful than younger ones? Many scientists are

inclined to answer: for pathological reasons. I don't share this

opinion, at least not for the major part of older people. It is not

just a question of loss of synapses, shrinkage of neuronal tissue, and

retraction of neuritic extensions. It is also a natural consequence of

accumulating meaningful information over very long periods of time. |

| Just

try to estimate the amount of data we are confronted with, day after

day. Each day has 86.400 seconds. At least during our sleep our brain

is shielded from the unabating influx of new information, but roughly

60.000 seconds remain. During a life of roughly 45 years duration, our

multiple sensory channels have been exposed for 1 billion seconds to

high resolution images and broad frequency sounds. Where did all this

material go? |

| Theoretically,

all this information could have gone all the way from our sensory

organs to

the primary receptive areas in the brain and from there to long-term

storage networks in our large cerebral association cortices.

Fortunately, this did not happen. The more experienced we got, the more

we learned to pay attention to the relevant signals and to

ignore the rest. Nevertheless, even by this strategic trick, our

association cortices got loaded with increasing amounts of information. |

| What

happens to this information? Is it just silently sitting there, just

waiting for the right moment to come?

Of course not. That would be a waste of storage capacity. It is on the

contrary actively participating in various thought

processes, concerning events that apparently have nothing to do

with the original

event that, a long time ago, was the first reason to set up this memory

trace. Our memory traces are always in motion, reverberating curiously

with each other and with new impressions. |

| Over

the years, the symphony orchestra in our brain gets larger and better.

More and more memory is accumulated, and if we are doing well and

succeed in making sense of all this stuff, it soon makes more sense

to listen to our inner voice than to follow each new external

impression. That's when our "forgetfulness" sets in. Our inner voice

gets more important than new information from outside. Again, we pay

more attention to the relevant thoughts (coming from inside ourselves)

and ignore most of the rest. |

| The

increasing forgetfulness of older people is the consequence of having

come to final solutions in multiple long-term thought processes. New

material is then often neglected either because it is recognized as

irrelevant and meaningless, or because it is allready known very well.

If something new appears on the scene that helps to improve the whole

complex construction, it is memorized very well, becoming an integral

part of our inner orchestra. |

3/12 < MB

(6/12) > 6/12

|