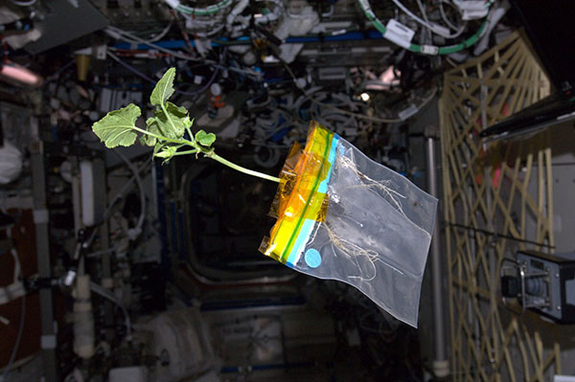

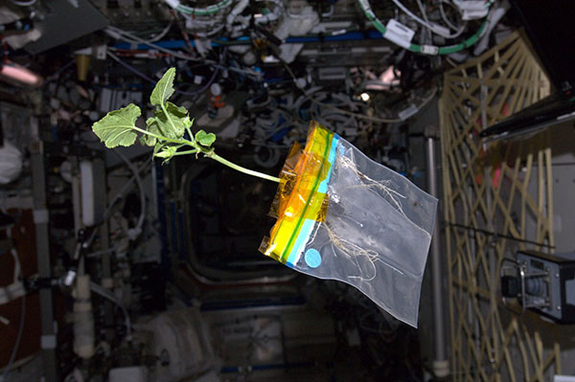

Zucchini plant grown on ISS (www.space.com)

Zucchini plant grown on ISS (www.space.com) |

| < A quest for space ship plants > |

| The International Space Station (ISS) is composed of several different modules, designed and produced by various nations. Recently, I've been shown around this spacious habitat by ESA's André Kuipers in a very agreeable way, and I recommend this 55 min video to scientists and to the lay public. I learned that this construction is a very busy and ambitious scientific laboratory, stuffed with tons of high-tech knick-knacks. |

| Orbiting 330 to 435 km above ground, the station is visited by space crafts several times a year. Usually, it is populated by 6 crew members staying in for up to 6 months. Very different from that would be the situation for a space colony destined to travel for several years to visit other planets of our solar system. The main purpose of such a station would be to enable the survival of its residents. The habitat would be encumbered only with instruments that contribute to such survival. |

| While all provisions essential for human life as oxygen, water and food can be transported regularly to the ISS, this will not be possible for a far away space colony. One person needs 0.84 kg oxygen per day (NASA); 3 times that quantity could be dispensed by a conventional oxygen bottle weighing 16 kg. To supply 3 astronauts by this way with oxygen for 3 years would require slightly more than 1000 bottles - a total weight of 16 tons. However, not even on ISS oxygen in pure form is brought in with heavy bottles, but is prepared from water by electrolysis. |

| Transported in the form of water, 3 persons would need 3 tons of water for a 3 years space flight just for breathing purposes. While it appears not totally improbable to bring such a quantity of water into orbit, you could make better use of it than just to breathe it away. During breathing, the oxygen is not annihilated, but combined with carbon to carbon dioxide, exactly that carbon dioxide photosynthetic organisms dream of. Why not invite some of them as company for our space flight? |

| You may think through all these life supporting possibilities, or you simply consult Winchell Chung's fascinating and extremely informative web site dealing with these topics in profound detail. You will learn that in principle space flights lasting for longer than a few months should try to set up a regenerating system. Recruitment of photosynthetic organisms would not only convert exhaled carbon dioxide back to breathable oxygen, but could also rechannel the carbon into edible products. |

| My main concern with all propositions for space colonies up to now, either purely imaginative or meant as serious scientific projects, are the huge investments into their construction and their maintainance. While such investments might be justified for easy to reach stations like the ISS, harbouring diverse and ever changing high end scientific experiments, a long-term far-away colony in space should be based on much simpler principles, for economic and for practical reasons. |

| The crew of such a colony cannot count on emergency visits from Earth if a problem arises. They need a robust construction that is easy to tinker around, with a high safety margin. Also, it should be sufficiently large to entertain a team of up to 20 people, but not depend on such a large crew. The station should be able even to cruise unmanned, on auto-pilot so to say, with continuous contact with Earth. My station would be set up in space from a few standardized building blocks that would be produced in high numbers. |

| Each building block should be easy to replace, with spare parts accompaning the station and without the need of complicated and demanding procedures. The station should stay in a permanent orbit. Propulsion would only be needed for orbit corrections, and to avoid occasional meteorids . The main missing part for such an autarc station is a functional photosynthetic module producing oxygen and fruits and vegetables. Such a module may be developed during the coming decades on ISS and its potential successor. |

| MB 7/13 |